Abstract

Subsequent malignant neoplasms (SMNs) are a common concern after treatment of primary cancer. Host-related factors, genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors, and treatment modalities contribute to the risk of SMNs. Patients with primary hematological malignancy (HM) are at an elevated risk for SMNs. However, many studies have concentrated on one or few specific hematological diagnoses and lack a comprehensive overview on the incidence of solid or hematological SMNs in primary HM patients. Our aim was to update and expand knowledge about SMNs after primary HM as reflected by better survival, possible changes in treatment-related late effects, and more recent classification of HMs.

A total of 44 087 patients aged ≥20 years and diagnosed with primary HM in Finland from 1992 to 2019 were identified from the Finnish Cancer Registry. We estimated standardized incidence ratios (SIR) and excess absolute risks (EAR) for any SMN, as well as for hematological and solid SMNs, separately. We analyzed and compared patient cohorts stratified by gender, age at primary HM diagnosis (20-40, 40-60, 60-80 and >80 years), and the diagnostic time period of the first primary HM (1992-1999, 2000-2008 and 2009-2019). The follow-up started 6 months after diagnosis of the first primary HM and ended at second primary cancer or end of 2020, death or emigration, whichever came first, and was classified as short (0.5-5 years) or long (>5 years).

Of the 44 087 patients with primary HM, 5121 patients (11.6%) suffered from SMNs (3923 solid SMNs, 1198 hematological SMNs). The SIR for hematological SMNs was overall 4.7 (95% confidence interval (CI) 4.4-5.0) compared to SIR 1.4 (95% CI 1.4-1.5) for solid SMNs. The SIR was similar in males and females (SIR 4.4, 95% CI 4.1-4.8 and 5.0, 95% CI 4.6-5.4 for hematological SMNs in men and women, respectively, and SIR 1.5, 95% CI 1.4-1.5 and 1.4, 95% CI 1.3-1.5 for solid SMNs in men and women, respectively). For all SMNs, as well as hematological and solid SMNs separately, the SIRs were highest in the young HM patients and decreased by age of first primary HM. However, the excess absolute risk was highest in the older patients, aged 60-80 years at their first primary HM.

Among patients diagnosed with primary HM at the age of 20-40 years, the SIRs for hematological SMNs were 9.1 (95% CI 6.5-12.4) in males and 11.0 (95% CI 7.3-15.8) in females whereas in those aged 80 years or more the SIRs were 2.0 (95% CI 1.4-2.8) in males and 1.8 (95% CI 1.2-2.5) in females. This finding was similar over short and long follow-up. The respective EARs were 1.6 and 1.4 in males and females, respectively, in the young patients aged 20-40 years, and 5.1 and 4.3 in male and female patients aged 60-80 years, respectively. This reflects the low absolute number of SMNs in young HM patients despite high SIRs, and the high absolute subsequent cancer burden comes from the older age groups.

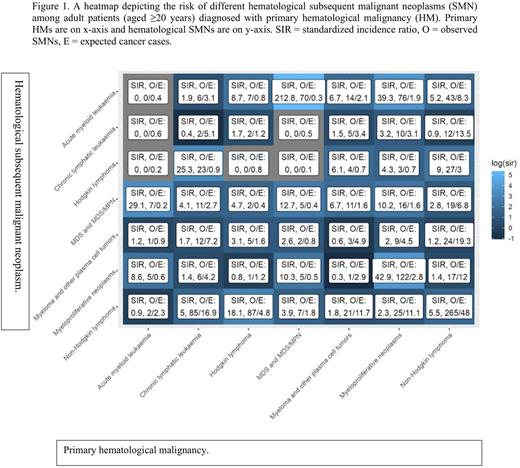

Besides a number of expected relationships between primary and secondary HMs, such as between myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), we also found some other interesting associations: patients with primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) had an increased SIR of 25.3 for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and patients with primary myeloma and other plasma cell tumors had an increased SIR of 6.7 for MDS (Figure 1).

In terms of absolute number of cancers, the most common solid SMNs following a primary HM were those of digestive organs, skin and respiratory organs. The highest SIRs for solid SMNs were for endocrine gland tumors (SIR 1.6, 95% CI 1.5-1.7), skin cancers (SIR 1.5, 95% CI 1.4-1.5), and for head and neck cancers (SIR 1.5, 95% CI 1.4-1.6). Solid tumors were mostly diagnosed >5 years after primary HM diagnosis.

In conclusion, the incidence of both hematological and solid SMNs were increased in hematological cancer patients. The strength of our study was that our follow-up was complete with no losses and included non-selected patients with SMNs also appearing shortly after the first primary HM diagnosis (0.5-5 years). Our results accentuate the need for vigilance in the surveillance of HM patients - also when diagnosed in the adulthood.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal